U.S. merchants have long chafed at the high cost of accepting credit cards. They’ve also seen little choice but to pay the growing fees, since the alternative would alienate many plastic-wielding customers.

But over the last seven years, a new option has gradually emerged, particularly for merchants that sell their wares to other businesses: imposing surcharges to recover the hefty interchange fees that they would otherwise pay to card network and banks.

The idea remains unpopular with credit card users, but it has become more feasible for many merchants as a result of rule changes by Visa and Mastercard, a favorable U.S. Supreme Court ruling and the emergence of new services that make it easier for businesses to impose surcharges.

“Now business operators are themselves seeing this proven out,” said Jonathan Razi, the CEO of CardX, which offers a service that enables merchants to impose surcharges on credit card purchases.

Merchants that signed up with CardX last year will save a total of $24.5 million annually by passing along card fees to customers, Razi said.

Until 2013, Visa and Mastercard prohibited merchants that accepted their cards from imposing surcharges. Even after the card networks revised their rules, it remained impractical for many merchants to charge higher prices for credit card purchases, since several of the nation’s largest states had laws that banned the practice.

The landscape has changed since the Supreme Court struck down New York’s anti-surcharge law in 2017. The justices found that the law violated merchants’ free-speech rights, since it allowed discounts to customers who pay with cash, which in practical terms is no different than a surcharge on those who pay with a card.

“That seemed to really create much more interest in the topic of surcharging,” said Scott Blakeley, an attorney in Irvine, Calif., who advises merchants on how to impose surcharges in a manner that complies with relevant laws and rules.

The high court’s ruling eventually opened the door for credit card surcharging not only in New York, but also in California, Florida, Texas, Maine and, most recently, Oklahoma. Last month, Oklahoma Attorney General Mike Hunter issued an opinion stating that the state’s anti-surcharge law would not survive judicial scrutiny.

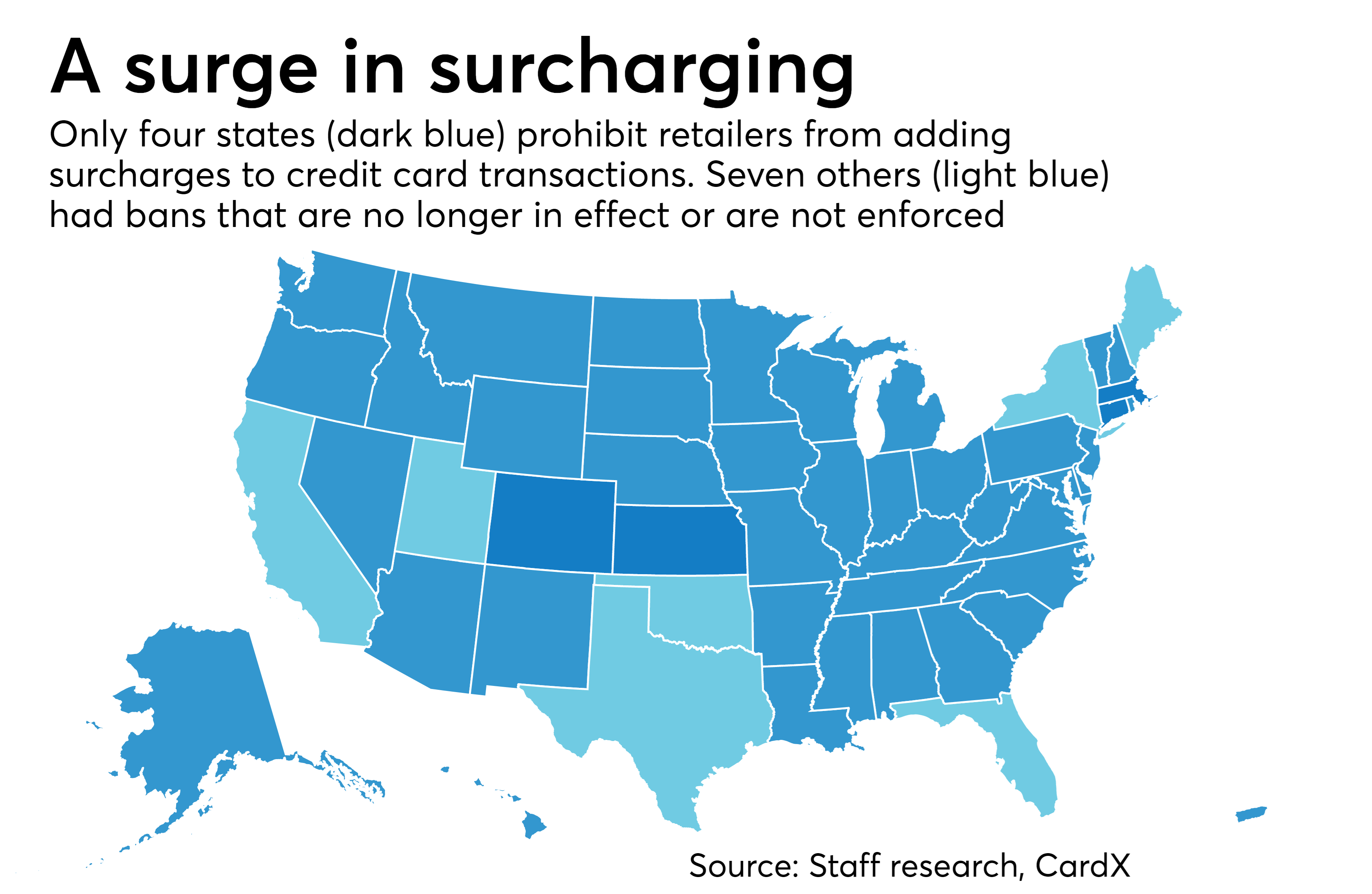

Today, only the anti-surcharge laws in Kansas, Colorado, Massachusetts and Connecticut are still viewed as impediments. And efforts are now underway to enable surcharging in those states.

Merchants may be more willing to consider surcharges as credit card payments become more common. Credit card payment volume in the U.S. was 56% higher in 2018 than it had been six years earlier, according to Federal Reserve data.

It is unclear how common credit card surcharging has become; there is no comprehensive publicly available data on its prevalence. Many merchants, especially those who cater to consumers, remain skeptical that surcharges will boost their bottom lines.

One concern in the retail industry is that surcharges will make it easier for card issuers and the card networks to continue increasing interchange fees. Another worry is that consumers will balk at the higher prices charged by merchants who tack fees onto credit card purchases.

“Whether they are allowed to or not, most retailers do not surcharge for credit card use, and most have no interest in doing so,” Stephanie Martz, senior vice president and general counsel at the National Retail Federation, said in an email.

“Retailers welcome the availability of software that helps them comply with surcharge laws, but the number who choose to surcharge remains very small.”

Spokespeople for Visa and Mastercard noted that merchants must comply with various rules if they want to surcharge but did not provide additional comment. A spokeswoman for American Express said that while the New York-based company generally does not prohibit surcharging, it believes the practice is harmful to consumers.

“It is not a customer-friendly practice for a merchant to attract a customer to its store or website to shop, and then to penalize the customer for using their payment method of choice,” the Amex spokeswoman said in an email.

Razi of CardX contends that surcharging is actually expanding the universe of merchants that accept card payments, which is beneficial to banks and the card networks. He said that the option appeals to some merchants that traditionally refused to accept credit cards because of the costs.

“Many of these merchants don’t even take cards until they have a chance to pass on fees,” he said.

CardX enables merchants to charge a 3.5% fee to credit card holders while taking steps to ensure that the merchants do not violate card network rules. For example, the Chicago-based company provides signage to merchants stating that surcharges do not apply to debit card purchases. CardX takes what is left of surcharge after the card-issuing bank and the card network get paid.

Payroc is a Tinley Park, Ill.-based payment processor that also offers surcharging to its merchant customers. John Barrett, an executive vice president at the company, said that surcharging has so far worked best in market segments where customers are less likely to leave because of the additional charge.

He mentioned charities as one example, since donors may not want their contributions to be defrayed by card fees. He also said that merchants that sell products primarily to other businesses are good candidates for surcharging, both because businesses’ supply chains are hard to change and also because many of these merchants have not accepted credit card payments historically.

“What the business is offering is the option,” Barrett said. Customers “don’t have to use the credit card.”

Staff Writer, American Banker